A Practical Guide to Home Heating Systems: Types, Efficiency, and Maintenance

Home heating feels simple when you twist a thermostat, but the choices behind that warmth shape comfort, costs, and emissions for years. This guide demystifies how systems work, compares common options, and highlights what efficiency ratings actually mean. You’ll see how climate, insulation, and sizing drive results more than hype. If you’re planning a replacement or just want lower bills, you’ll find clear steps to decide, maintain, and upgrade with confidence.

Staying warm isn’t just about turning on the heat—it’s about choosing a system that fits your climate, home, and goals for comfort, budget, and sustainability. Heating is often the largest energy expense in cooler regions, so the technology under your roof matters. In this guide, we move from fundamentals to practical decisions and upkeep, emphasizing clear, data‑backed comparisons and real-world trade-offs rather than hype.

Outline of the article:

– Heating fundamentals and how heat moves through a home

– Comparing major system types: furnaces, boilers, heat pumps, and radiant

– Efficiency metrics, energy sources, and environmental impact

– Sizing, climate, and the building envelope

– Maintenance, costs, and a practical upgrade roadmap (conclusion)

Heating Fundamentals and Distribution Explained

All heating systems aim to replace heat lost from your home to the outdoors. That loss happens through conduction (heat passing through walls, windows, and roof), convection (air leaks carrying warmth away), and radiation (surfaces exchanging heat). A well-chosen system works in tandem with insulation and air sealing to slow losses while delivering steady, controllable warmth. Understanding distribution—the path heat takes from the equipment to your rooms—helps you predict comfort and efficiency before you invest.

Most homes rely on one of two distribution approaches: moving warm air or moving warm water. Forced-air systems heat air and push it through ducts to registers, and hydronic systems heat water and send it through baseboards, radiators, or in-floor tubing. Radiant approaches, particularly heated floors, warm surfaces so people feel comfortable at lower air temperatures. Each pathway affects comfort: air systems respond quickly but can feel drafty, while hydronic and radiant systems are slower to change but offer an even, enveloping warmth.

Distribution details to consider:

– Duct location: ducts in attics or crawlspaces can lose 10–20% of heat if uninsulated or leaky.

– Zoning: multiple thermostats can reduce energy use by heating only the areas you occupy.

– Air quality: filters and balanced airflow can cut dust and improve indoor conditions.

– Response time: radiant floors heat surfaces gradually; forced air reaches setpoints faster.

Control strategies also matter. A single-stage heater simply cycles on and off, which can cause temperature swings, while modulating or multi-stage equipment tailors output to the moment, often improving comfort and reducing noise. Thermostat placement is critical; a thermostat near a heat source or sunlight can misread conditions, causing short cycling and uneven warmth. Finally, the building envelope—insulation level, window performance, and air sealing—sets the baseline; tighter, better-insulated homes need less heat, enabling smaller equipment that runs more efficiently and quietly.

Comparing Major System Types: Furnaces, Boilers, Heat Pumps, and Radiant

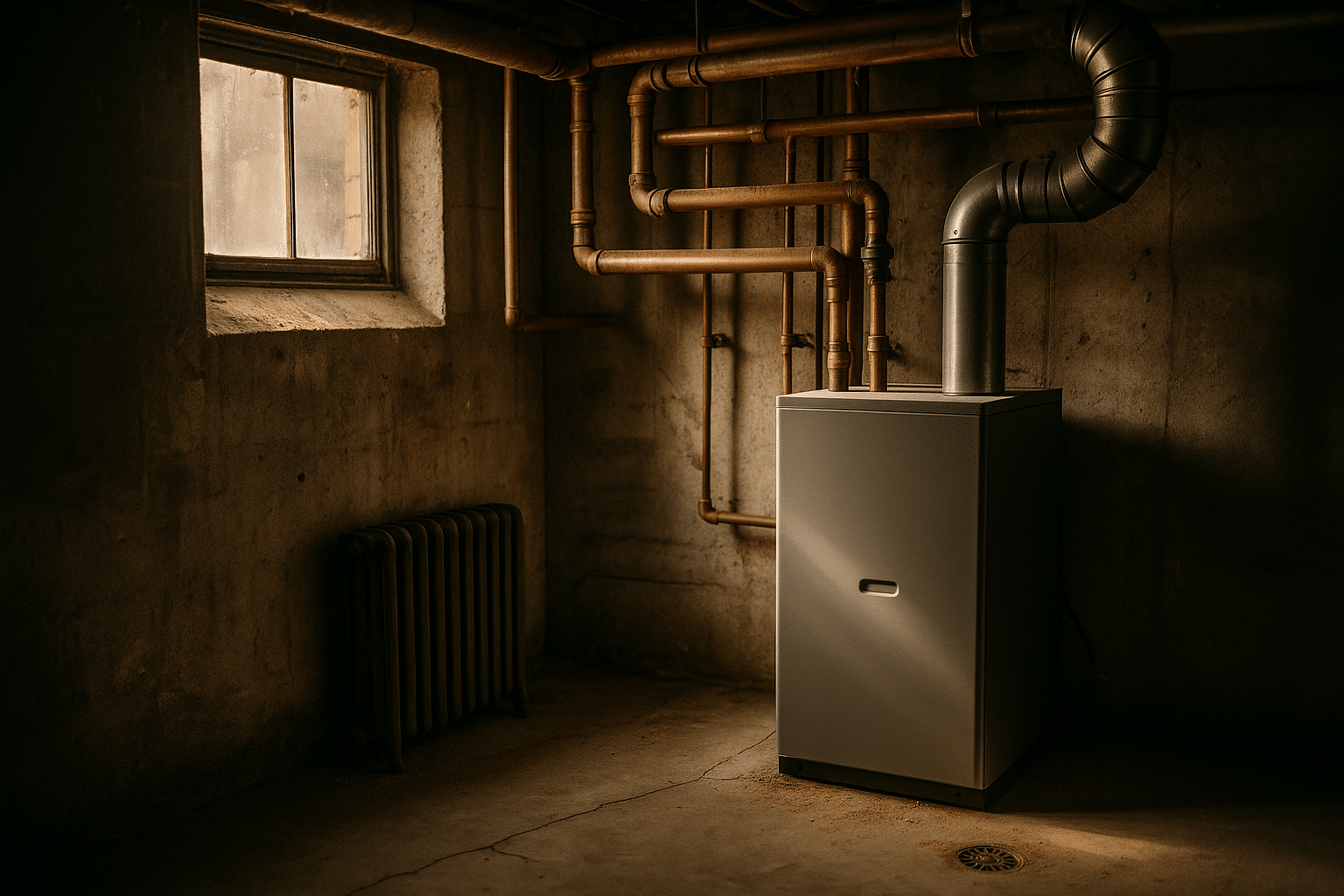

Furnaces burn fuel (or use electric resistance) to heat air that moves through ducts. They are common in regions with existing ductwork, and they pair easily with central cooling. Fuel-fired models vary by efficiency, from legacy units in the low 80% range to high-efficiency condensing designs above 90%. Electric resistance furnaces are simple and compact but can be costly to run where electricity prices are high. Typical lifespans range from about 15 to 20 years with regular maintenance.

Boilers heat water for baseboards, radiators, or radiant floors. Many homeowners appreciate the steady, quiet heat and the lack of moving air; hydronic systems also avoid duct leakage. Modern condensing boilers can achieve efficiencies in the 90%+ range when paired with low-temperature emitters like radiant floors. However, radiators and piping increase installation complexity, and retrofits can be more involved than swapping a furnace. Boilers often last 20–30 years with proper care, though circulator pumps and valves may need periodic replacement.

Air-source heat pumps move heat instead of creating it by combustion, delivering two to four units of heat for every unit of electricity in typical conditions. Cold-climate designs maintain useful output well below freezing, and variable-speed compressors help sustain comfort without frequent cycling. Ducted heat pumps can reuse existing ductwork; ductless options serve additions or homes without ducts. Ground-source (geothermal) systems tap stable earth temperatures for higher efficiency but require drilling or trenching and carry higher upfront costs. Lifespans vary: 12–20 years for air-source outdoor units, with ground-source loop fields lasting decades.

Radiant floor systems deliver heat through warm surfaces, reducing the need for high air temperatures and minimizing stratification. Hydronic radiant pairs well with high-efficiency boilers or heat pumps using low-temperature water. Electric radiant mats are straightforward for single rooms like bathrooms but can be expensive to run over large areas. Installation is easiest during new construction or major remodels; retrofits may require floor height changes or careful planning to avoid adding excessive mass.

Quick comparisons:

– Speed vs. smoothness: forced air heats quickly; hydronic and radiant feel steadier.

– Retrofit friendliness: furnaces and ducted heat pumps slot into existing ducts; hydronic and radiant often require more work.

– Fuel flexibility: furnaces and boilers depend on local fuel availability; heat pumps rely on electricity and benefit as grids get cleaner.

– Noise: modern variable-speed heat pumps and sealed combustion furnaces are typically quiet; hydronic is often near-silent at the point of use.

Efficiency Metrics, Energy Sources, and Environmental Impact

Efficiency labels can look cryptic, but they point to real differences in performance. Fuel-fired furnaces and boilers use AFUE (Annual Fuel Utilization Efficiency). An 80% AFUE unit delivers 80% of the fuel’s energy as heat to the home; a 95% AFUE unit delivers 95%. Heat pumps use HSPF (Heating Seasonal Performance Factor) or COP (Coefficient of Performance). A seasonal COP of 3 means the system supplies three units of heat per unit of electricity on average, a key reason heat pumps can be cost-effective in many climates.

Choosing an energy source requires balancing price stability, availability, and emissions. Electricity’s emissions vary by region and are trending downward as more renewables come online. A national average in many places has ranged roughly 0.7–1.0 pounds of CO₂ per kWh, but local values can be much lower or higher depending on the grid mix. Combusting natural gas emits about 11–12 pounds of CO₂ per therm, while heating oil is higher per unit of heat. Because heat pumps multiply the heat from each kWh, their effective emissions per delivered unit of heat can be substantially lower than electric resistance or some combustion options, particularly on cleaner grids.

Operating cost math is straightforward if you normalize to the heat you actually get indoors. Convert each fuel to cost per MMBtu delivered by dividing fuel cost by efficiency. For example:

– If electricity is $0.16/kWh and a heat pump’s seasonal COP is 3, the cost per delivered kWh is roughly $0.053 (since 1/3 of $0.16), or about $15.50 per MMBtu.

– If natural gas is $1.50 per therm and your furnace is 90% AFUE, delivered cost is about $1.67 per therm-equivalent, or roughly $16.60 per MMBtu.

– If heating oil is $4.00 per gallon and the boiler is 85% efficient, expect higher delivered costs per MMBtu compared to efficient electric heat pumps or gas in many markets.

Other considerations:

– Part-load performance: variable-speed equipment often raises seasonal efficiency beyond nameplate values.

– Distribution losses: uninsulated ducts in unconditioned spaces can erase theoretical gains.

– Venting and safety: sealed combustion reduces backdraft risks and can improve indoor air quality.

– Future-proofing: as grids decarbonize, electrically driven systems tend to become cleaner over time.

Sizing, Climate, and the Building Envelope: Choosing What Fits

The right system size is the foundation of comfort and efficiency. Oversized heaters short-cycle, create uneven temperatures, and can be noisier. Undersized systems struggle in cold snaps and may rely on expensive backup heat. The industry-standard approach is a room-by-room heat loss calculation that considers square footage, insulation levels, window area and type, air leakage, orientation, and local design temperatures. Rules of thumb can miss the mark by a wide margin, especially in renovated or well-insulated homes.

Climate guides the playbook. In milder regions, air-source heat pumps can cover most or all heating with high seasonal efficiency. In cold climates, cold-ready heat pumps, hydronic systems, or high-efficiency furnaces are common choices. Humidity and ventilation matter, too; homes with high infiltration benefit from air sealing and balanced ventilation, which can reduce heating loads enough to downsize equipment and improve comfort.

Example scenarios:

– A 2,000 ft², well-insulated home in a moderate climate might see peak heat needs under 20,000 BTU/h, making a modestly sized heat pump practical.

– The same home in a cold climate could require 35,000–45,000 BTU/h depending on envelope quality and infiltration.

– An older, leaky 2,000 ft² home with single-pane windows may exceed 50,000 BTU/h until upgrades (air sealing, attic insulation, window improvements) cut losses.

Distribution affects sizing, too. Ducts should be right-sized and sealed; insufficient return air or crushed flex duct raises static pressure and reduces delivered heat. Hydronic emitters must be matched to water temperature; if you want a condensing boiler to actually condense, use larger radiators or radiant floors to run lower water temperatures. Heat pumps benefit from careful airflow setup and refrigerant charge verification to achieve rated output and efficiency.

Decision checklist:

– Start with envelope improvements: air sealing, attic insulation, and weatherstripping often pay back quickly.

– Select equipment after a proper load calculation, not before.

– Consider zoning for multi-story homes or large footprints.

– Match distribution to lifestyle: quicker recovery for intermittent occupancy, or radiant steadiness for all-day comfort.

Maintenance, Costs, and a Practical Upgrade Roadmap

Even high-efficiency equipment underperforms without regular care. Basic maintenance reduces breakdowns, preserves warranties, and keeps bills predictable. For forced-air systems, replace or wash filters on schedule; dirty filters raise static pressure, reduce airflow, and increase energy use. Inspect ducts for leaks and insulation gaps, especially in attics or crawlspaces. For boilers, bleed radiators if needed, check system pressure, and schedule periodic flushes to remove sludge. Heat pump owners should keep outdoor coils clear of debris, maintain proper drainage, and ensure defrost cycles operate correctly.

Suggested maintenance rhythm:

– Every 1–3 months: check filters and registers; clear returns; trim vegetation around outdoor units.

– Each season: test thermostats, inspect venting for corrosion, and verify safety controls.

– Annually: professional inspection for combustion safety, heat exchanger integrity, refrigerant charge, and airflow; clean burners or coils as appropriate.

– After storms or renovations: recheck ductwork, exterior terminations, and clearances.

Upfront costs vary widely by region and scope. Typical installed ranges (not including incentives and subject to local pricing) might look like:

– High-efficiency furnace: roughly $3,000–$7,000 with duct reuse.

– Boiler with baseboards: about $6,000–$12,000 depending on piping complexity.

– Air-source heat pump (ducted or ductless): around $5,000–$12,000 depending on capacity and zones.

– Ground-source heat pump: approximately $18,000–$35,000 due to drilling or trenching.

– Hydronic radiant floors: often $10–$20 per square foot in remodels, less in new builds if planned early.

Payback depends on fuel prices, climate, run hours, and the quality of your installation. Envelope upgrades can reduce equipment size, lowering upfront costs and operating expenses simultaneously. Many regions offer rebates or tax incentives for high-efficiency equipment and weatherization; check current local programs and permit requirements before starting.

Conclusion: homeowners’ roadmap

– Fix the envelope first: air seal, insulate, and address moisture management.

– Confirm your loads: commission a room-by-room heat loss calculation.

– Choose a system that fits your climate, distribution, and comfort preferences.

– Plan for maintenance: simple habits preserve efficiency and extend life.

– Revisit in five years: as grids evolve and technology improves, new opportunities may emerge.

With a clear understanding of how heat is made, moved, and managed, you can select a system that keeps your home comfortable, trims energy use, and aligns with your long-term plans. Thoughtful sizing, careful installation, and routine care turn complex technology into everyday comfort—quiet, reliable, and ready for the seasons ahead.